We have better things to do than worry about whether you’ll change in time to get our business. Business is only a part of our lives. It seems to be all of yours. Think about it: who needs whom?

Is this still a relevant ‘theses’ ten years on?

Let’s start with ‘business is only a part of our lives. It seems to be all of yours’. There is undoubtedly a gulf between a marketer’s work-life and their social-life. In Marketing and Modernity, an ethnographic study of a Swedish pizza company in the 1990s, Marianne Elisabeth Lien states that ‘practically nobody ever enters the marketing department as consumers. Yet the department is filled with people who are all part-time consumers in their various private capacities’ (original emphasis). This moment of realisation leads her to conclude that as far as marketers are concerned ‘consumers are the ‘ultimate other’’.

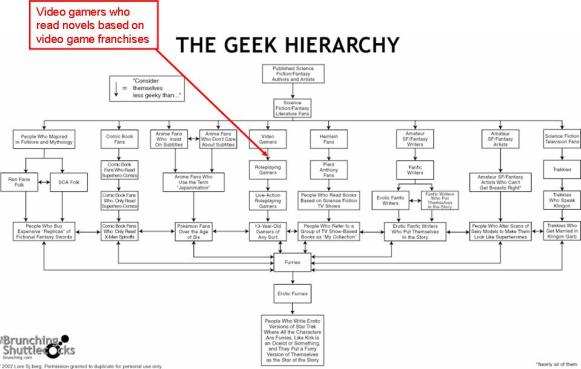

Has anything changed since Lien conducted her fieldwork in 1991/92 long before the internet became the mass phenomenon it is and even longer before global brands took an interest in what the internet could do for them? The answer, on the surface, is probably not. Marketing language may be changing to reflect the latest marketing trends, at least in a supplemental way, but the view most marketers prefer of consumers is the one from a distance. Why is this? At a superficial level it’s probably got a lot to do with the culture of most marketing departments, but at a more profound level it has got more to do with the concept of the ‘consumer’ and where it’s expected to sit in the grand hierarchy of life.

Lots of research companies claim not to like the word ‘consumer’ but ultimately ‘consumer’ is a category we tend to put people in if they don’t work in our industry, after all we might ask them about their family, their job, their hobbies, but inevitably we’re interested in what they buy and why. Of course the interesting thing about the term consumer is that nobody really thinks of themselves as a consumer, we may occasionally find ourselves admitting that we are under duress, but beyond the odd ironic slogan t-shirt we see ourselves as much richer subjects than that implied by the term. Despite the importance of consumption in our lives, we tend to see only the act of making a purchase as consumption, once we get our goods home and put them away in their proper place the act of consumption ceases. In light of this it’s understandable why the term consumer has an underlying pejorative meaning, it suggests an individual who puts more value in the act of purchase itself rather than the value of the object purchased. It’s always been a safe way to maintain the status quo, business is what the clever people do, consuming is what the stupid people do. When David Ogilvy in Confessions of an Advertising Man, published way back in 1963, says ‘the consumer isn’t a moron; she’s your wife’, he’s kidding no-one. But things have changed. The reason marketing teams aren’t encouraged to think like consumers is because all that separates them from the commodity obsessed masses is their sales sheets and knowledge of industry jargon. It’s simply safer to pretend that these tentative pieces of cultural capital will hold the dogs at bay.

For the majority of large businesses the growth of the web has done little to change this attitude, if anything the consumer has become an even more unnerving figure, inevitably distorted through media hype of the latest web trend and its most bizarre accounts. But even the companies founded on the web seem to have a rather ambivalent attitude to their consumers – for example, Facebook’s attempts to monetise users so far has ranged from disastrous to ineffectual. So simply being a successful web brand isn’t enough to guarantee an enlightened attitude to the humble consumer. The even sadder fact is that this attitude isn’t exclusive to business people, the people we classify as consumers think consumers are stupid. The Conversation on the web isn’t quite what it was, even in 1999 The Cluetrain Manifesto lamented the loss of innocence ‘Today, we tend to think of “flaming” as a handful of people vociferously insulting each other online. A certain sense of finesse has largely been lost. In the olden days, a good flame war could go on for weeks or months, with hot invective flying around like rhetorical shrapnel’. Having been a part of the great social network site exoduses of the early 21st century I can remember distinctly the allure of Myspace with its legal band profiles, fully customisable html and I can also distinctly remember the jaded comments of friends who were sick and tired of the spam filled inboxes on Myspace, to whom Facebook was a beacon of light. That a lot of this spam came not from businesses as such but bands, club nights, self promoting individuals is no longer a surprise but it was more so at the time. If the web had been all about the conversations, it was rapidly heading in the direction of self-promotion. It seems that rather than businesses becoming more like consumers, consumers were becoming more like businesses. Thanks to the communicative and distributive tools of the internet anybody could advertise themselves and lots of people did. This trend has only accelerated – players of online games form hierarchical top-down organisations, techies develop apps in their spare time, ebay and amazon encourage people to become virtual stores. Even the less commercially minded will cumulatively spend hours updating profiles and uploading photos. If the sprawling chaos of the Myspace profile was the infomercial, Twitter is the streamlined 30 second ad where detail is less important than impact. No wonder business tries to distance itself from consumers when they threaten to move into the territory they’ve spent so long cultivating as their own.

I’m not saying this is a bad thing, the internet gives us greater control over what we consume and how we consume it and theoretically it’s great that anyone can become a business person, but the manner in which most people go about promoting themselves is rooted in over a century of traditional media and traditional media’s tactics, it suffers from the same problems and assumptions, particularly about what consumers will respond to. Hence the proliferation of spam. In the tradition of alternative histories it could be argued that the past 20 years should be known as The Age of Spam. Unlike advertising which has always been the medium of business, spam is the democratised take on one way messaging en masse. If spam was just the tool of the Viagra sellers then it would simply be another form of advertising, the fact that your friends and acquaintances are also more than happy to participate in a bit of ad hoc spamming is what differentiates it from its predecessors. In fairness to the people of the web, there are few proven alternatives to the traditional media format and let’s face it the traditional media approach works even if it’s far from perfect.

Possibly the greatest threat to businesses then is that it is being gradually commoditised, if everyone can do it then the position of expert is eroded if not erased. Perhaps the most insistent example of this is the music industry. When consumers and bands found that it was possible to distribute music more efficiently than the record companies, the music industry’s status was significantly reduced. The situation is hardly helped by programs like The X-Factor or Britain’s Got Talent where members of the public are raised to pop star status overnight only to be worthless a month later. It suggests that musical ability and talent is something the public at large are just as capable of discovering as the so called experts.

Finally then ‘who needs whom?’ Consumers, or whatever we call them, still need business, so much of our lives is based around the production, distribution and social status of commodities but business is no longer the behemoth it was it is worth only as much as its latest product or ad campaign, business is having to work harder to matter to people. What does business need to do to change this state of affairs? Well The Cluetrain Manifesto argues that business needs to find its human voice, to be genuine, pure, honest, but if the human voice on the web is intractably coloured by decades of marketing speak then it would seem rather foolish for business to attempt to follow this lead. After all it’s very difficult for sprawling corporations to appear genuinely human, a Facebook profile, Youtube page and Twitter account isn’t really enough to convince us of this. Instead business needs to wow us and amaze us like it did in the post war years with its modern miracles. Business is too content to follow trends set by consumers, when it should be starting the trends or at least trying to. Hopefully this would give marketing departments greater confidence in their own abilities rather than feeling like their place in the world has been usurped by the masses and consumer will cease to be such a derisory term. I think when businesses start aiming to be the experts again that then they will be ready to have a real conversation with consumers about what they are doing and what they should be doing because they’ll have an opinion and the confidence to debate its worth.